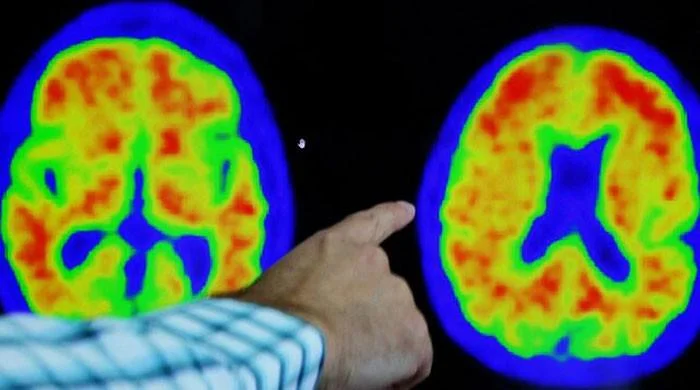

Two new drugs, called “lecanemab” and “donanemab”, are gaining significant attention as the first is capable of slowing down the debilitating progression of Alzheimer’s disease.

However, while their defenders view them as a significant breakthrough in medical research, critics view them as another disappointment after a series of costly failures.

“We have turned a corner” thanks to these treatments, British biologist John Hardy, who has been studying Alzheimer’s since the 1990s, told AFP.

Rob Howard, a professor of old age psychiatry at University College London and a critic of the drugs, said: “I think that the drugs have been used to raise false and unrealistic hopes in people with Alzheimer’s disease and their families.”

These opposing statements sum up the entrenched positions on the recently introduced drugs for Alzheimer’s, the most common form of dementia which millions of people across the world suffer from.

Lecanemab, sold under the name Leqembi, was developed by US pharma firms Biogen and Eisai. Donanemab, developed by pharma giant Eli Lilly, is sold as Kisunla.

The controversy has seen countries take different stances on whether to approve the drugs or not.

The United States gave the green light to lecanemab in 2023, then donanemab earlier this year. However, the European Union rejected lecanemab in July, a bad omen for donanemab’s chance of approval.

Last month, the UK steered a middle course, approving the use of lecanemab but not making it available on the state National Health Service.

What no one denies is that the two drugs are the most effective Alzheimer’s treatments ever but their effectiveness is limited.

Both appear to reduce cognitive decline in patients at the onset of their disease by around 30%, which seems high but represents a relatively small difference over the year-and-a-half period when the studies were carried out.

“The benefits are so tiny as to be practically invisible in an individual patient,” Howard said.

Expensive

Critics argue that the drugs, that can sometimes cause brain swelling or bleeding, are not worth the risks and are highly expensive.

At the prices being charged by Biogen and Eisai in the US, lecanemab would cost 133 billion euros if given to all eligible patients in the EU, according to a 2023 study.

Meanwhile, advocates of the drugs, including many neurologists, believe they can offer patients a few more precious months of autonomy and that the effectiveness of the drugs could be multiplied if patients started taking them earlier in the disease’s progression.

This could soon be more practicable as research on diagnosing Alzheimer’s more quickly has recently been making significant strides.

The differing national policies could also mean that poorer patients are left behind.

“We will see rich people going to the US” for the drugs, Hardy said.

The debate can be traced back in part to a seminal 1992 article by Hardy about how the disease actually works.

The article argues that clumps of protein called amyloid plaques — a constant in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients — are not just one element among others, but the main factor triggering the disease.

Over the decades, many drugs targeting these amyloid plaques were developed, all of which failed — until lecanemab and donanemab.

Pressure from families

The scepticism from some quarters about the new drugs could be because the previous ones were defended and even lauded by some, despite their ineffectiveness.

Christian Guy-Coichard, the head of French organisation Formindep which monitors medical conflicts of interest, accused Alzheimer’s groups, researchers and pharmaceutical firms of being too close.

But France Alzheimer deputy director Benoit Durand said that very little of its funding came from Biogen/Eisai or Eli Lilly, instead pointing towards pressure for new treatments from patients’ families.

“They don’t understand” the EU’s decision to turn down a breakthrough new drug, Durand told AFP. He also feared that laboratories could lose interest in Alzheimer’s disease due to the setbacks.